Chapter 2

Chapter 2 – Summer Subsistence – Fosse à l’Anguille, 14th Century

Fosse à l’Anguille [Eel Pool] is located upstream of the Canyon des Portes de l’Enfer on the Rimouski River, in the Duchénier Wildlife Reserve. The area is still accessible today and its name remains unchanged, commemorating its long history as an eel-fishing site for Indigenous families. The river’s topography concentrated eels in this area, allowing families to fish large quantities that could serve as winter provisions.

Origines

In the 14th century, Indigenous peoples occupied the entirety of the Americas, from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego. It’s theorized that their ancestors arrived from Asia about 15,000 years ago, crossing the Bering Strait between Siberia and Alaska. At that time, the northern half of the continent was covered in enormous glaciers that stretched as far south as what is now New York. This ice sheet trapped enormous quantities of water on the continent, to the point that ocean levels dropped, leaving a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska known as Beringia, which remained open for tens of thousands of years.

As the glaciers retreated about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, populations of hunter-gatherers who had dispersed throughout the continent were able to travel northward, from the southern half of the continent towards what is now Quebec.

In the 14th century, the total Indigenous population in the Americas was in the millions, while that of what is now eastern Canada is estimated at a few hundred thousand individuals.

However, the specific ethnic distinctions among the populations who inhabited what is now the Lower St. Lawrence region are still unknown. For this reason, we have opted to refer to them using the generic term “Algonquian peoples,” in reference to Proto-Algonquian, the common ancestor of their languages. Later, this language would branch into several relatively distinct dialects: those spoken by the Innu people (referred to as Montagnais by the French colonists), the Mi’kmaq (also referred to as the Canadiens, Gaspésiens, or Micmacs by the French) and the Wolastoqiyik (also referred to as the Etchemins or Maliseet by the French).

Environment and Economy

The natural environment, made up of forests, lakes, rivers, and the enormous St. Lawrence River, afforded abundant and varied resources for the Algonquians. They primarily travelled by canoe or on foot using paths (portages), some of which had been in use for millennia.

The populations throughout the continent were connected by a vast trade network, giving different groups access to resources otherwise unavailable in their area. Their daily lives were structured by the seasons and by migration throughout immense forested areas. They lived according to their own rules built on respect for the land and for all living things.

Roles of Men and Women

Among the Algonquians, the men had primary responsibility for hunting, fishing, equipment preparation, and homebuilding. Women took care of carrying game back to camp, gathering firewood, and preparing the birch bark that was used to cover wigwams. Men also built canoes and snowshoes, while women made clothing, prepared hides, cooked food, and tended the fire.

According to ethnologist Marc Laberge, women often gave birth by themselves, either in a hut specifically reserved for this purpose or in the forest. Women remained active until the moment of birth and returned to their normal activities within a short time. Children were nursed until the age of four or five, at which point they were given more freedom and became a shared responsibility of the community. Once they were old enough to eat solid food, their mothers would help them by chewing meat for them. Women generally had three or four children, and births were often cause for celebration. Babies would be carried in a nagaan, or cradleboard, which was decorated with many round beads and shell bracelets or necklaces.

Language and Culture

Each Indigenous people has its own language, customs, beliefs, and rituals. The Algonquians hunted, celebrated, played, and built; they made clothing, tools, and weapons; they fought on occasion, and they travelled a great deal. Their knowledge and traditions were passed down orally to their children. Between the ages of 6 and 14, boys spent a great deal of time learning to hunt and fish, and making tools such as bows and arrows, which they would use to hunt birds. Girls would imitate the work their mothers did: butchering meat, preparing food, tanning hides, making clothing, and harvesting berries.

Indigenous peoples generally wore clothing made of animal hide and often painted their faces or tattooed their skin, in addition to piercing, cutting, or wearing decorations on their ears. To protect their skin and hair from mosquitoes and the sun, they would cover themselves with grease or other oily substances. For some rituals, they would wear headdresses made from leather bands and decorated with feathers, antlers, or other items. Around their necks, Algonquian people wore necklaces bedecked with animal claws, feathers, seashells, turtle shells, or other items brought back from the hunt or from battles with other nations. Women used matachias — body ornamentation, made in this case with ochre, a natural pigment — to paint their bodies for celebrations or rituals.

Homes

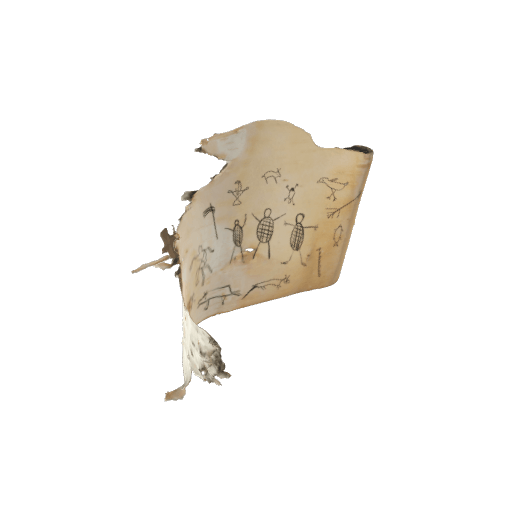

The Algonquians of the St. Lawrence estuary lived in huts, wigwams or other temporary shelters made from wooden poles and covered with birch bark, or pine branches if birch was unavailable. Women used ochre to decorate their homes with drawings of a variety of animals, such as birds, moose, otters, and beavers.

When setting up a campsite, the Algonquians generally chose a place near water: by a lake or at the mouth of a river. In winter, the men packed down the snow with their snowshoes and covered the ground with fir boughs. Winter dwellings were smaller than summer ones, with a space in the centre for a fire. Packs were generally stored against the branch-covered walls, while meat from fish and small mammals was hung from overhead beams to dry and cure.

In the summer, maritime Algonquian peoples built larger shelters that could hold several fires. Samuel de Champlain reported in 1603 that he entered one house at Tadoussac in which over 80 people were gathered around several fires. Inhabitants of the Lower St. Lawrence region didn’t live in villages, but sometimes in small assemblages of dwellings, especially during summer gatherings.

In short, the Algonquian people made use of whatever materials they found as they moved to quickly build shelter for the night.

Canoes with Sails

While some sources contend that sails on Indigenous canoes only appeared in the 1400s, we opted to add them to our illustrations of the canoes that hunted marine mammals on the St. Lawrence. The sails were probably made from moose hide, although this remains hypothetical, for no Indigenous writings or drawings have been found confirming such a use at that time. According to John Jennings, the first sail used might have been a leafy bush brought aboard to catch the wind.

References

Laberge, M. (with Girard, F., ill.) (1998). Affiquets, matachias et vermillon [Affiquets, matachias and vermillon]. Recherches amérindiennes au Québec.

Leclercq, C. (1999). Nouvelle relation de la Gaspésie, édition critique sous la direction de Réal Ouellet [New relations of Gaspésie, critical edition directed by Réal Ouellet]. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Goddard, I. (1979). Eastern Algonquian Languages. In B. G. Trigger, & W. C. Sturtevant (éds.), Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 15: Northeast). Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

Trudel, M. (2018). Mythes et réalités dans l’histoire du Québec [Myths and realities in Quebec’s history]. Bibliothèque québécoise.

Taché, J.-C. (1876). Trois légendes de mon pays ou l’évangile ignoré, l’évangile prêché, l’évangile accepté [Three legends of my country, or the ignored gospel, the preached gospel, the accepted gospel]. Imprimerie A. Côté et Cie.

Jennings, J. E., & Adney, T. (2012). Bark Canoes: The Art and Obsession of Tappan Adney. Firefly Books.