Chapter 4

Trade between Nations – Le Bic, 15th Century

In this sphere, located in Cap à l’Orignal in the Bic region, we find ourselves inside of a longhouse. Before the arrival of Europeans, this model of dwelling was typical for nations that were part of the Iroquoian culture and language group, serving as important spaces in which Indigenous peoples lived and conducted ceremonies, political meetings, or various community gatherings.

Archeological Information

Archeological research has found that a rectangular house was built and inhabited during the Woodland period, between 3,300 and 4,000 years ago, at the present-day site of Parc du Bic. However, this was not a village of longhouses as was found at Stadacona and Hochelaga. Instead, the house stood alone.

In a report on the findings made at the site, archeologist Pierre Dumas wrote:

“The structure would have been 4.4 metres wide and at least 7.1 metres long … It could plausibly have housed about ten people, in all likelihood divided into two families.

The tools found inside suggest that various tasks related to preparing food, processing leather, and woodworking would have been carried out in the home.”

Nations and Linguistic Families that Visited the Estuary

The nomadic peoples of North America spent millennia covering vast distances to hunt, fish, forage, and trade, and would travel along the St. Lawrence River and its downstream tributaries, including the Saguenay River, the Rivière du Loup, the Rimouski River and the Trois-Pistoles River. These rivers also afforded access to other large river systems, including the St. John River, which empties into the Bay of Fundy at what is now St. John, New Brunswick, or the Restigouche and Miramichi rivers. Using these interconnected rivers, Indigenous peoples could travel south to Maine and Chaleur Bay, west to Stadacona and Hochelaga, north to Saguenay and east to the Gaspé Peninsula, towards such traditional gathering places as the Bic archipelago and the Trois-Pistoles region.

The peoples who most regularly used the estuary region for travel and subsistence were the St. Lawrence Iroquoians and the Algonquians. The Iroquoians who used the river for subsistence and trade came from the area that is now the City of Québec. In the family of Algonquian-speaking nations, the primary groups present in the area were the Wabanaki (Abenaki) and, to the southeast, from the Gaspé Peninsula towards Maine and the Maritimes, the Wolastoqiyik and the Mi’kmaq. Those who inhabited the region to the north of the St. Lawrence were (from east to west) the Innu (Montagnais), the Atikamekw, and the Algonquin (part of the larger Anishinaabe subgroup of the Algonquian peoples).

Travel and Trade

Thanks to trade and travel, nations could diversify the resources available to them. For example, it was possible to obtain corn and wild rice from the sedentary peoples to the south, lithic (stone) material from what is now Labrador for tools and weapons, and large mammal hides and marine products from the St. Lawrence estuary.

Large Gatherings

The size of gatherings varied according to the type of event. These gatherings generally happened at the same places and around the same time of year.

Gatherings were held to commemorate a successful hunting trip, the birth of a child, or the death of a group member. When several distinct families were present, these gatherings were often the sites of intermarriage arrangements. Trade, which made it possible to build reserves of food, hides, and materials of all kinds, was essential for these nations, as they did not all have access to the same resources.

Lastly, such gatherings also were opportunities to build alliances through marriage or to rebuild relationships that had been soured by disputes, raids, or old squabbles.

Customs

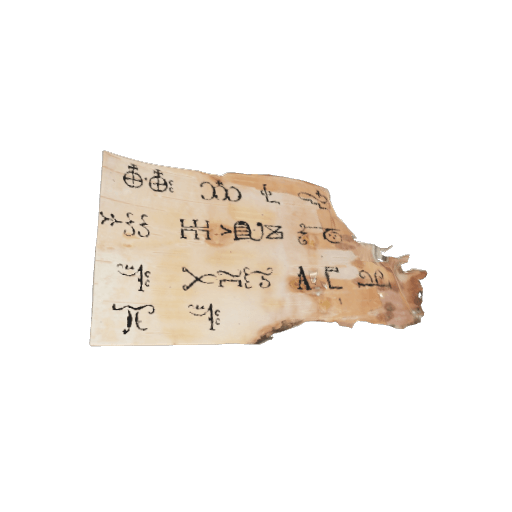

In the 1400s, the First Nations had their own languages, customs, and rituals. They had not yet been influenced by European explorers.

Trade

Trade among different nations was frequent. Trading took place either at gatherings or on an individual basis. For example, makers of arrowheads or spears might travel hundreds of kilometres to trade their goods. Both nomadic and sedentary nations made use of their skills and resources. While some might grow corn or make pottery, others had access to large birch trees, porpoises, or cervids (moose, caribou and deer). Someone who knapped stone, wove baskets, or tanned hides might produce a larger quantity than what they needed, with the goal of exchanging their surplus for goods that they could not otherwise find or produce.

Distribution of Winter Hunting Grounds

Every summer, the distribution of hunting grounds for the coming winter was re-evaluated. Negotiations were carried out to balance the distribution of hunting grounds among the families in a given region, based on the density of large game in the area. The chiefs who determined this distribution were generally the best hunters of the group. While families generally respected this distribution, a hunting party that had a poor season might ask another family for the right to hunt on their land. As it was poorly viewed in Algonquian societies not to share one’s resources or goods, hospitality was in order.

Marriages

During large summer gatherings, marriage arrangements were prepared. Once agreements had been made, a location was chosen and the ceremonies were announced in advance, to be celebrated the following summer or in two years’ time. Such celebrations were larger affairs.

Among the patrilocal or patrilineal Algonquian nations, it was customary for a husband’s family to welcome his new wife. In contrast, among the matrilocal or matrilineal Iroquoian nations, it was the wife’s family who took in her new husband.

Conflict

Tensions could arise within or between communities, if, for example, hunting grounds were disputed, an incursion was made into borderlands, a nation sought to control certain trade items, or a nation demanded a right of way through another’s territory or a share of the trade goods that passed through it.

When such rivalries could not be resolved through diplomatic channels, war could break out. Wars between nations involved violent and bloody acts, but also provided an opportunity for young warriors to demonstrate their courage and bravery, thus gaining prestige in their community. However, such acts were not a regular custom.

Reconciliation and Diplomatic Rituals

During summer gatherings, diplomatic rituals served to ease tensions or rebuild peaceful relationships. Quarrelling parties would smoke tobacco from a pipe together to de-escalate the situation. They would exchange gifts of different kinds, inviting one another to forget their grievances or, if the conflict had led to losses, to “cover the dead” and ease the pain of grieving families.

A feast would be organized to close these ceremonies. Traditional dishes like sagamité and bannock would be prepared and offered to all, and games, dances, songs, and drumming would enliven the event.

References

Dumais, P. (1988). Le Bic: Images de neuf mille ans d’occupation amérindienne [Le Bic: Pictures of nine thousand years of Indigenous occupation] (Ethnoscop, vol. 64). Ministère des Affaires culturelles.

Bouchard, S. (2017). Récits de Mathieu Mestokosho, chasseur innu [Tales of Mathieu Mestokosho, Innu hunter]. Boréal.

Bouchard, S. (2013). Confessions animales: Bestiaire [Animal confessions: Bestiary]. Bibliothèque québécoise.

Laberge, M. (with Girard, F., ill.) (1998). Affiquets, matachias et vermillon [Affiquets, matachias and vermillon]. Recherches amérindiennes au Québec.